Surrogacy in Taiwan: Reflections Inspired by What Money Can’t Buy

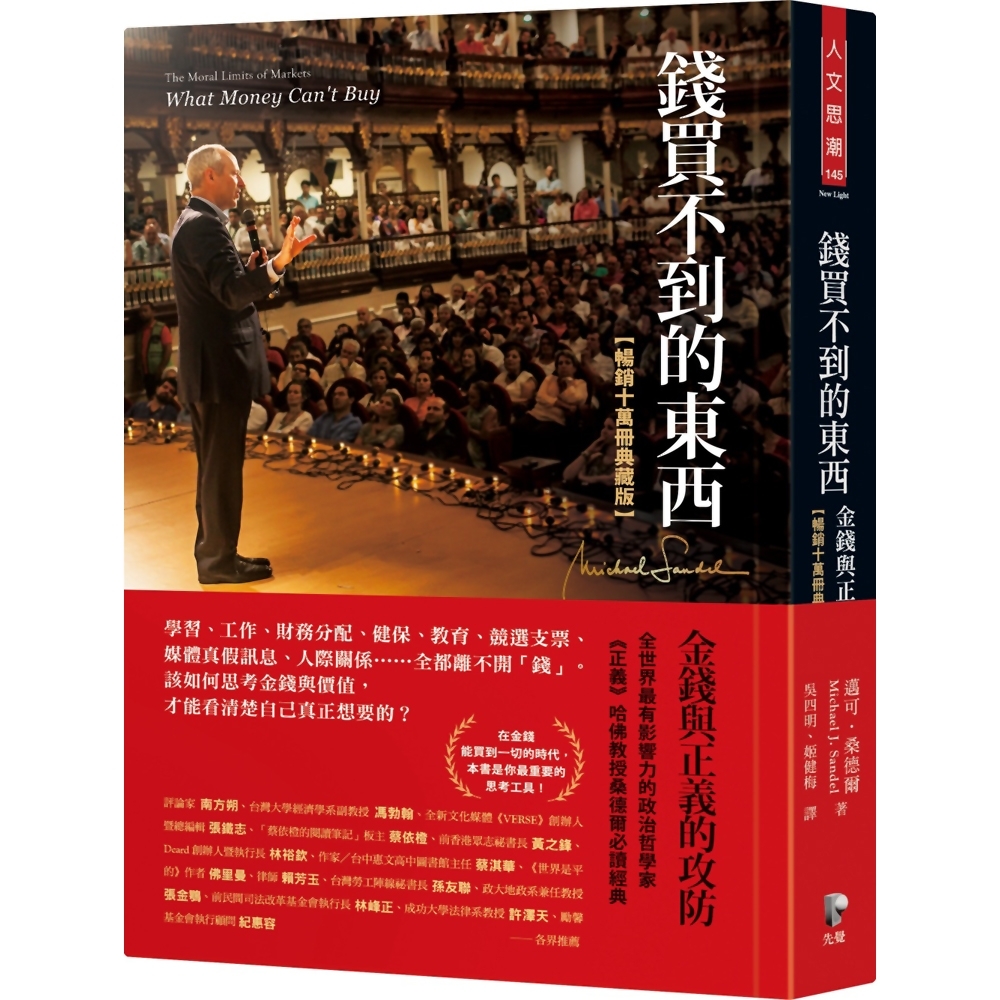

Recently, Taiwan’s Legislative Yuan has been debating the legalization of surrogacy, sparking discussions about its ethical, social, and legal implications. While some argue that surrogacy offers hope to families struggling with infertility, others are concerned about its potential to exploit women, especially those from disadvantaged backgrounds. These debates led me to reflect on Michael Sandel’s book What Money Can’t Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets, which challenges us to question the role of money in areas traditionally governed by moral and social values.

During these discussions, an unusual and, in my view, problematic comment was made by legislator Chen Chao-Tzu. She stated in an interview, “The Virgin Mary was a surrogate mother. If children belong to God, then all mothers are surrogate mothers.” While this comment may have been intended to support surrogacy, I believe it oversimplifies a complex issue and diverts attention from the important ethical considerations surrounding it.

In his book, Sandel explores how introducing market logic into every aspect of life risks eroding values like fairness, dignity, and human relationships. Surrogacy is a perfect example of this dilemma. When a woman’s womb is treated as a commodity, what does that mean for how we view motherhood and the creation of life?

Supporters of surrogacy argue that it is fair and consensual, as both parties agree to the arrangement. However, Sandel reminds us that consent is not always enough to ensure fairness, especially when one party is in a position of economic disadvantage. This is a critical issue for Taiwan’s lawmakers: how can they ensure that surrogacy agreements protect women’s rights and prevent exploitation, particularly of vulnerable individuals?

Another concern is how surrogacy may change the meaning of parenthood and relationships. In some cases, commercial surrogacy might reduce childbirth to a transactional process, diminishing the emotional and social significance of bringing a new life into the world. For example, should Taiwan only allow altruistic (non-commercial) surrogacy, where financial compensation is not the primary motivation? And how can we provide better legal and emotional support for surrogate mothers and the children born from these arrangements?

Sandel’s book also examines broader questions about justice and morality. He emphasizes that some things, such as human dignity, should not be bought or sold at any price. Surrogacy raises these exact questions: where should we draw the line between market freedom and moral responsibility?

Taiwan’s current debates on surrogacy offer us a chance to reflect on what kind of society we want to build. It’s not just about creating a new law—it’s about protecting core values like respect, fairness, and humanity. The decisions made today will not only shape the future of surrogacy in Taiwan but also reflect how we, as a society, balance progress with ethics.